John Betjeman’s Dublin whispers

Document of the month: FO 898/70/475-6

Guy Woodward investigates poet John Betjeman’s role in spreading rumours in neutral Ireland during the Second World War.

This comes from a short run of documents in the PWE archive, found in the innocuously-named file FO 898/70 ‘Procedure, General Correspondence And Reports’. It is a copy of a note intended for the poet John Betjeman, dated 20 July 1942. At this time Betjeman was serving as British press attaché in Dublin, capital of neutral Ireland, where he had arrived in January 1941. The post was cover for his work for the Ministry of Information – in Spying on Ireland (2008), historian Eunan O’Halpin describes Betjeman’s role as twofold: firstly, to cultivate the Irish press to foster sympathetic coverage of Britain’s progress in the war, and secondly to counter Axis propaganda in Ireland.[1] This second responsibility involved intelligence gathering, as Betjeman analysed news sheets produced and distributed by the German and Italian legations in Dublin for their content and provenance.

On arrival in Ireland Betjeman threw himself onto the Dublin social scene, cultivating friendships with journalists, civil servants, artists and writers, including Seán Ó Faoláin, Frank O’Connor and Patrick Kavanagh. In her cultural history of Ireland during the war, That Neutral Island (2007), Clair Wills writes that six months after his arrival Betjeman was ‘a well-known and popular figure, frequently encountered in the pub, and at house parties and literary functions.’[2]

In 1942 Betjeman became ‘PWE’s chosen instrument in Dublin’ when he agreed to assist in the spreading of ‘sibs’.[3] The word derives from the Latin ‘sibillare’, meaning to hiss or whisper – sibs were rumours invented and disseminated with the aim of deceiving the enemy, of undermining enemy morale, or of damaging perceptions of the enemy (read more about sibs here).

According to O’Halpin, as ‘an inveterate gossip’ Betjeman was ‘an obvious though perhaps too conspicuous choice for the clandestine task of whispering’.[4] Nevertheless, his use was approved by the controller of SOE; SIS and MI5 were also consulted.

This letter is headed ‘Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office’ at Bush House, Aldwych in London. The PID was a genuine research department in the Foreign Office, but was used as a cover name by the PWE even after the closure of the real PID in 1943 (this presents difficulties for historians and archivists – read more about the names used by PWE here).[5] Bush House was the home of the BBC European Service but also housed the secret headquarters of the PWE – handy for liaising with the BBC, although relations were sometimes fractious.

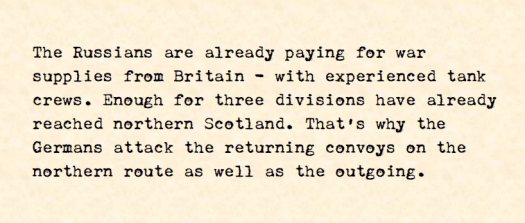

The letter is unsigned, but preceding documents in the file suggest it was written by John Rayner, a member of the Underground Propaganda Committee involved in the production of rumour, in response to a request from Betjeman to pass on ‘any interesting stories that were going about’. Rayner summarises six of these. One reads:

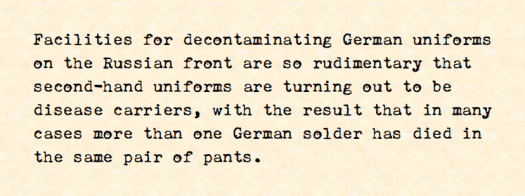

Another reads:

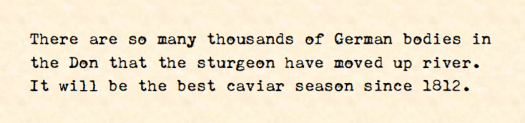

And another states:

These stories tap into public fascination with the Eastern front, following the entry of the Russians into the war on the side of the allies in 1941: at home in Britain many were elated by this, and in occupied Europe the new front presented a new point of emphasis for the propagandists. The macabre details of the second and third rumours are also significant – historian of British psychological warfare Charles Cruickshank writes of sibs that ‘Few ordinary people can resist the temptation to pass on bad news, a human weakness on which the whispering campaign relied for much of its success.’ For a rumour to be successful, he suggests, ‘it should be alarming enough to have to be passed on, and credible enough to conceal the fact that it was a fabrication.’[6] A note from Rayner to a Captain Wintle dated 6 October 1942 reflects this definition, suggesting that sibs for Ireland should be restricted to ‘“verities” or near-verities’.[7]

It is unclear whether Betjeman received the list of ‘stories’. Another note written from Rayner to Betjeman and dated four days later on 24 July expresses the hope of sending ‘a few beans to spill under separate cover in a few days’ but cites ‘unexpected difficulties which have prevented my doing so before’ – it is possible therefore that the note of 20 July was never sent.[8] Due to the destruction of many records in the PWE archive (one account suggests only one tenth of the material was retained) we are also missing records of the sibs that Betjeman himself was charged with spreading.[9]

We do know that he recruited George Furlong, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland, as a vehicle for disseminating these, however. Usefully Furlong had strong social links with the Italian legation in Dublin and also visited London regularly on business, occasions on which sibs could be conveyed to him verbally.[10]

In August 1943 Betjeman returned to England, where he worked at a secret department of the Admiralty known as P branch in Bath.[11] Reporting his planned return on its front page on 14 June 1943, the Irish Times hailed Betjeman for seeing it his duty not only ‘to interpret England to the Irish, but also to interpret Ireland sympathetically to the English’.[12]

Follow us at @PWEpropagandist for #siboftheweek, where we’ll be posting some of the best ‘sibs’ from the PWE archive.

Notes

All archival material is Crown Copyright and is held in The National Archives. Quotations which appear here have been transcribed by members of the project team.

[1] Eunan O’Halpin, Spying on Ireland: British Intelligence and Irish Neutrality During the Second World War, (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 138.

[2] Clair Wills, That Neutral Island: A Cultural History of Ireland During the Second World War (London: Faber and Faber, 2007), p. 186.

[3] O’Halpin, p. 210.

[4] O’Halpin, p. 210.

[5] Ellic Howe, The Black Game: British Subversive Operations Against the Germans During the Second World War, (London: Queen Anne/Futura, 1988; orig pub 1982), p. 1, p. 42.

[6] Charles Cruickshank, The Fourth Arm: Psychological Warfare 1938-1945, (Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 108.

[7] FO 898/70/469.

[8] FO 898/70/471.

[9] Howe, p. 7.

[10] O’Halpin, p. 212.

[11] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: https://doi-org.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/30815

[12] Quoted in Alex Runchman, ‘English perceptions of Irish culture, 1941-3: John Betjeman, Horizon, and The Bell’ in Irish Culture and Wartime Europe, 1938-1948, ed. by Dorothea Depner and Guy Woodward (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2015), pp. 87-98 (pp. 87-8).