VE Day: the PWE and the POWs

Document of the Month: FO 898/330

James Smith and Guy Woodward on the PWE’s re-education of POWs

“The Italian prisoners are gratified at the part played by the Partisans in the liberation of Northern Italy and derive from it hopes of a rebirth of Italian prestige. Many co-operators, who apparently failed to appreciate that their presence among crowds celebrating the Victory might not be welcome, resented not being allowed to mix with the public on VE-Day”

These lines appear in a May 1945 report by the PWE’s ‘Prisoners of War Directorate’ on the morale of Italian Prisoners of War (POWs) held in camps in Britain.

The PWE papers shows that rather than marking the end of the PWE’s role, VE Day raised new problems for branches of the agency tasked with the ‘re-education’ of POWs – even those who welcomed the Allied victory.

Like its First World War predecessor Crewe House, the PWE’s role in the production of propaganda for enemy and occupied Europe made it a natural choice for overseeing the re-education programme of captured enemy prisoners.[1] During the war the PWE had made extensive use of surveys of POWs to assess the efficacy of various types of propaganda; the agency’s John Baker White suggested that ‘Prisoners were of the utmost importance in psychological warfare, being the mirror to the morale that P.W.E. and P.W.D. were seeking to destroy.’[2]

Several POWs were also employed to voice radio broadcasts to their home countries: Agnes Bernelle, a refugee who performed as ‘Vicki’ on the black station Soldatensender West recalled that German POWs were brought to the studio blindfolded to read news reports.[3]

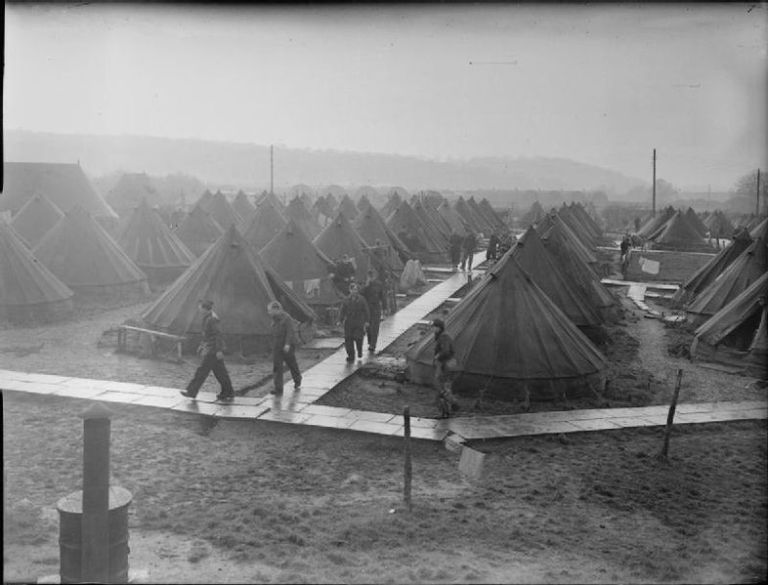

Documents record that by May 1945 there were 154,513 Italian and 199,543 German and Austrian, POWs held in camps in Britain, and that numbers actually increased over the following year.

The PWE’s Prisoner of War Directorate monitored the ‘screening’ of prisoners into ‘white’, ‘grey’, or ‘black’ ideological categories, and/or into ‘co-operator’ and ‘non-co-operator’ groups. ‘White’ co-operators with needed qualifications were prioritised for repatriation to help in the rebuilding of their home countries, whereas ‘black’ POWs were moved to separate camps and attempted to be converted.

A range of books, newspapers, lectures, English lessons and other materials were organised to aid the re-education process. The PWE was particularly concerned to communicate to German POW’s what had happened in Nazi concentration camps: in June 1945 all German prisoners were obliged to attend a screening of a 20 minute film on the camps; audience monitoring surveys showed ‘that the film has made a profound impression on the prisoners and is accepted, with some negligible exceptions, as a genuine record of Nazi barbarity.’

The PWE recorded that a small number of German NCOs spread ‘the opinion that the film was faked’ however, and one report states that ‘a large minority of the prisoners – mainly of course, in the “Black” camps’ refused to believe the films as they ‘are still under the influence of Nazi propaganda and clinging obstinately to Nazi ideas’ – showing, perhaps, that the cry of ‘fake news!’ to dismiss unpalatable facts is far from new, and indicating that the effects of wartime propaganda would endure long after 8 May 1945.

The photos accompanying this piece were taken by a Ministry of Information photographer documenting daily life in a German POW camp in Britain in 1945 and are part of the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

Notes

[1] Sir Campbell Stuart, K.B.E., Secrets of Crewe House: The Story of a Famous Campaign (London, New York, Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1920), p. 143.

[2] John Baker White, The Big Lie (London: Evans Brothers, 1955), p. 105.

[3] Agnes Bernelle, The Fun Palace (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1996), p. 95.