Postcard propaganda: Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin

Document of the month: FO 898/123

Guy Woodward finds echoes of PWE campaigns in Hans Fallada’s novel Alone in Berlin

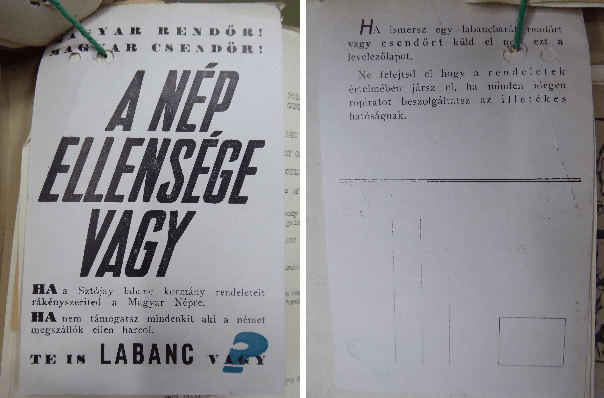

One of the most ingenious and darkly humorous items I have found in the PWE papers is this postcard designed for distribution in Hungary in 1944. Circulating Allied propaganda was of course prohibited in Axis states, and punishments were severe, but the postcard attempted to circumvent and subvert the laws against this. It addresses itself to police officers, advising them that if they are enforcing the orders of the German-backed Hungarian government they are acting as ‘Enemies of the People’. The card advises anyone who finds it to send it to any ‘policeman or gendarme’ they knew, and features the reminder: ‘Don’t forget that you are acting in accordance with official instructions if you surrender all foreign leaflets to the competent authority.’[1] The card clearly aims to undermine the authority of the police, but was paradoxically perfectly legal to circulate.

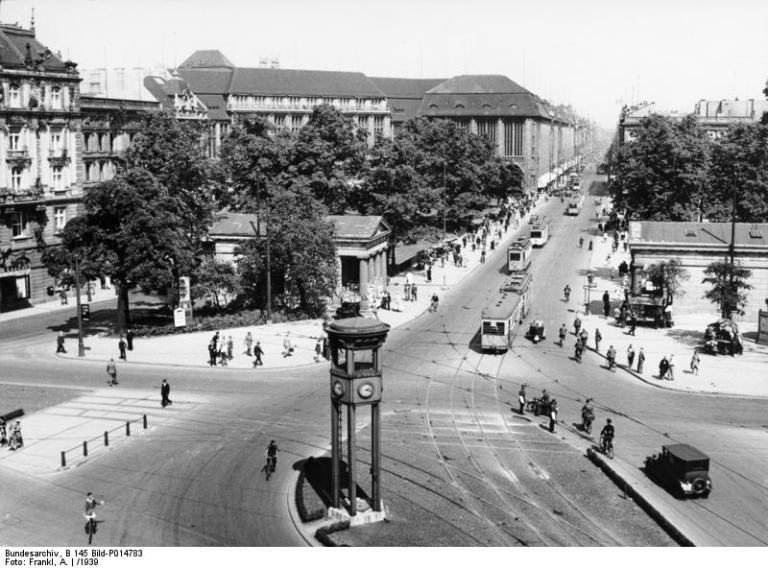

I was reminded of this postcard when reading Hans Fallada’s novel Alone in Berlin, originally published as Jeder stirbt für sich allein in Germany in 1947 (Michael Hoffman’s celebrated English translation did not appear until 2009). The novel focuses on Otto and Anna Quangel, a working-class couple in Berlin in 1940, who are shaken from their plodding and acquiescent existence when their son Ottochen is killed fighting in France. After much thought, Otto Quangel decides to express his newfound resistance by producing anonymous postcards critical of the Nazi regime and dropping them in stairwells of buildings around the German capital. His wife Anna is initially unimpressed by the plan:

And what was he proposing? Nothing at all, something so ridiculously small, something so absolutely in his character, something discreet, out of the way, something that wouldn’t interfere with his peace and quiet. Postcards with slogans against the Führer and the Party, against the war, for the information of his fellow men, that was all.[2]

For those interested in the material and affective qualities of wartime propaganda the novel features much of interest. Fallada describes Otto’s production of the initial postcard in considerable detail: he wears gloves to prevent giveaway fingerprints, and writes laboriously in a block capital ‘sign-writing style’ rather than cursive script more likely to betray his hand.[3] Before dropping the card, which features the bleak opening line ‘Mother! The Führer has murdered my son’, Otto and Anna discuss what is likely to happen when it is discovered.

Anticipating that some cards will be handed in straight away to apartment block wardens or to the police, Otto remains upbeat:

‘…whether it’s shown to the Party or not, whether to an official or a policeman, they all will read the card, and it will have some effect on them. Even if the only effect is to remind them that there is still resistance out there that not everyone thinks like the Führer…’[4]

The following chapter describes the nerve-shredding business of dropping the card – using gloved hands again, Otto deposits the card on the inner window sill of an office block. Attention then switches to the discovery of the card by film actor Max Harteisen; out-of-favour with Joseph Goebbels after contradicting the Reich Minister of Propaganda, Harteisen is thrown into total panic when he finds the card near the office of his attorney:

Sweat beaded on his brow, suddenly he understood that it wasn’t just the writer of the postcard, but also himself, who was in danger of his life, and perhaps he even more than the other! His hand itched: he wanted to put the card down, he wanted to take it away with him, he wanted to tear it to pieces, just where he was…[5]

Otto’s postcards promote ideas familiar to historians of the PWE – the first card opens by accusing Hitler of murder but continues to advise readers to obstruct the German war effort through a quiet programme of non-compliance and malingering:

DON’T GIVE TO THE WINTER RELIEF FUND! – WORK AS SLOWLY AS YOU CAN! – PUT SAND IN THE MACHINES! – EVERY STROKE OF WORK NOT DONE WILL SHORTEN THE WAR![6]

These injunctions are strikingly similar to those emphasised in British propaganda campaigns: official historian David Garnett described the malingering booklet produced in various forms by the PWE’s Black Printing Unit as the agency’s ‘most important publication’, and the PWE would expend considerable energy in attempting to persuade German military personnel and labourers to feign injury or run covert go-slow campaigns in factories and mines.[7]

Otto Quangel’s ambitions are grandiose; at the outset he tells Anna that ‘We will inundate Berlin with postcards, we will slow the machines, we will depose the Führer, end the war’.[8] These dreams are doomed, however: very few of the several hundred cards produced pass into circulation, and we learn towards the novel’s end that almost all were immediately handed in to the authorities.

Much of the narrative follows Gestapo Inspector Escherich’s patient pursuit of the Quangels over several months, as he notes the locations in which the postcards are found on a map on his office wall. The culprits are eventually revealed when a card slips accidentally from Otto’s bag at the factory where he works (originally this produced furniture but now, chillingly, it has been turned over to the manufacture of coffins for the Eastern front). At this point Fallada drops a small but significant hint acknowledging the circulation of Allied propaganda in Germany at this early stage of the war, in the form of a rumour which immediately begins circulating on the shop floor: ‘What was that you were reading a moment ago, boss? Was it really a British propaganda leaflet?’[9]

I can find no further reference connecting Fallada to British propaganda. Geoff Wilkes’s afterword to the Penguin edition of Alone in Berlin states that Fallada’s US publisher, Putnam, arranged transport to England for the author and his wife Anna in late 1938, but that at the last moment he decided he could not leave Germany; the couple spent the war on a smallholding in Carwitz, fifty miles north of Berlin.[10]

However, the novel certainly suggests that in tone and style PWE campaigns reflected (and perhaps sought to mimic and inspire) those conducted within Germany – Alone in Berlin is based on the true story of Elise and Otto Hampel, a Berlin couple who conducted a three-year postcard propaganda campaign following the death of Elise’s brother in combat.[11] And most notably, this suspenseful thriller provides a gripping imagined account of the risks and dangers involved in producing and circulating printed propaganda on the ground in enemy territory, a topic understandably often absent from historical records.

Images by kind permission of The National Archives

Notes

[1] FO 898/123.

[2] Hans Fallada, Alone in Berlin, trans. by Michael Hoffman (London: Penguin, 2009; orig. pub. 1947), p. 139

[3] Ibid., p. 141.

[4] Ibid., p. 144.

[5] Ibid., p. 157.

[6] Ibid., pp. 156-57.

[7] David Garnett, The Secret History of PWE: The Political Warfare Executive 1939-1945 (London: St Ermin’s Press, 2002), p. 191. There is an informative page on the malingering campaign on Lee Richards’s invaluable website: https://www.psywar.org/malingering.php

[8] Fallada, p. 144.

[9] Ibid., p. 396.

[10] Geoff Wilkes, ‘Afterword’ to Fallada, p. 575.

[11] Fallada, n.p.