Letters in bottles and leaky U-boats: Ian Fleming’s ideas factory

Document of the month: FO 898/6/64-5

Guy Woodward traces the involvement of the creator of 007 in covert wartime propaganda

This is a memo dated 18 January 1940 – it reports on a recent meeting of the ‘Consultative Committee’ of the Department of Publicity in Enemy Countries. This department was part of Electra House, a secret body under the control of the Foreign Office, responsible for clandestine propaganda in the early stages of the war – before the foundation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in July 1940 and the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) in September 1941.

The meeting discussed a number of ‘sibs’ – rumours invented to spread misinformation – but also makes a series of references to Lieutenant Ian Fleming, later creator of James Bond, then serving in the British Naval Intelligence Department (NID).

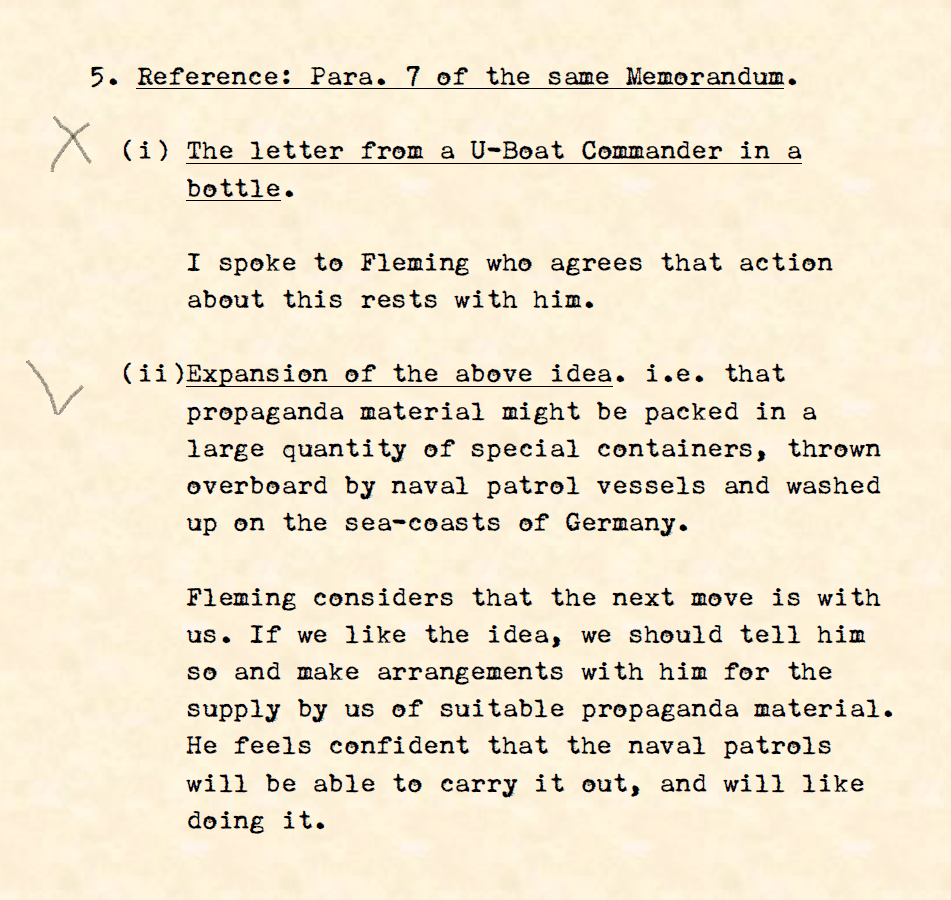

We read first about a mysterious plan involving a ‘letter from a U-Boat Commander in a bottle’:

It is unclear what the first plan involved – there are no other references in the archive to letters in bottles – but we can speculate that moves were afoot to produce a fake letter from a U-boat commander to be thrown into the sea, which would mislead its intended German recipients (the cross marked beside the proposal suggests that this was never enacted anyway). The second plan is more straightforward, involving the dissemination of propaganda material to Germany via containers dropped at sea. Ian Fleming’s assertion that sailors on naval patrol ‘will like’ doing this is striking however, an expression of adventurousness and derring-do at odds with the cold formality of many of these departmental records – and indicative of the approach he took to his own role.[1]

Indeed, the plans cited here are very much milder than some of the schemes which Fleming hatched in the early stages of the war. In For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond (2008) Ben Macintyre writes that ‘Some of Fleming’s ideas were run-of-the-mill, some were fantastical and impractical, and some, in the opinion of his colleagues, were simply mad.’[2] These included:

scuttling cement barges in the Danube at its most narrow point in order to block the waterway for German shipping; forging Reichsmarks to disrupt the German economy; dropping an observer (possibly Fleming himself) on the island of Heligoland to monitor the shipping outside Kiel; luring German secret agents to Monte Carlo and capturing them; and floating a radio ship in the North Sea to broadcast depressing and/or irritating propaganda to the Germans.[3]

Although Fleming would later dismiss such plans as ‘nonsense’ and ‘romantic Red Indian daydreams’, the fact that they were considered indicates the operational leeway afforded naval intelligence, before the foundation of SOE and before the fall of France and consequent Battle of the Atlantic dictated other naval priorities. Through Fleming, NID continued to be involved in the formulation of propaganda, however.

Fleming had been recruited in May 1939 by Admiral John Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence and widely credited as inspiration for ‘M’ in the James Bond novels. Working from the ‘ideas factory’ – room 39 in the Admiralty – Fleming developed his schemes and liaised officially and unofficially with a wide circle of military personnel, agents and propagandists.[4]

The PWE’s Sefton Delmer had known Fleming as a journalist before the war, and recalls in his memoir Black Boomerang, being introduced by his friend to Godfrey, who was excited by the potential of ‘black’ radio stations as a means of attacking the morale of U-boat crews. Both Godfrey and Fleming proved enthusiastic supporters of Delmer’s methods.

Delmer explains this naval enthusiasm (as opposed to the frequent hostility of the army and RAF to propaganda activities) with reference to the fact that the Royal Navy had been engaged in all-out war from the beginning of the conflict in 1939, when army and air force remained engaged in the phoney war. He notes that the navy were also unique among the services in having direct contact with the enemy from the beginning of the war, as they captured German prisoners at sea. Interrogations of these prisoners provided valuable intelligence material, later used by Delmer’s propagandists in crafting black propaganda such as the Soldatensender Calais radio station, intended to undermine the morale of U-boat crews.[5]

Fleming’s linguistic skills even enabled him to make direct contributions to such outlets, voicing commentaries on special programmes aimed at sailors of the Kriegsmarine broadcast by the BBC German Service and telling a friend ‘You may have heard my austere tones […] telling the Germans that all their U-boats leak.’[6]

Many connections can of course be drawn between Fleming’s wartime activities and his later creation of British secret agent 007 – the ability to conceive a compelling scenario and a predilection for imaginative and unorthodox methods are certainly clear assets in the fields of propaganda and of popular fiction. Delmer, whose name appears in a passing reference in Fleming’s Diamonds are Forever (1956) certainly suggested that his friend had drawn on his involvement with the PWE, writing that:

I sometimes wonder whether he did not pick up something for his thriller writing from our ‘black’ propaganda technique in return. For our first clandestine radio ‘Gustav Siegfried Eins’ and later our counterfeit German soldiers radio ‘Soldatensender Calais’ we used the most meticulous minutiae, taking care to get them exactly right , street numbers, technical terms, nicknames, and what have you, so that the deception itself would gain acceptance through their accuracy.[7]

Notes

All archival material is Crown Copyright and is held in The National Archives. Quotations which appear here have been transcribed by members of the project team.

[1] The RAF were notably sceptical about the value of dropping propaganda leaflets from the air and were often reluctant to facilitate drops over enemy territory. See Tim Brooks, British Propaganda to France, 1940-1944: Machinery, Method and Message, (Edinburgh University Press, 2007), p. 37 and David Garnett, The Secret History of PWE: The Political Warfare Executive 1939-1945, (London: St Ermin’s Press, 2002), p. 188.

[2] Ben Macintyre, For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond, (London: Bloomsbury, 2008), p. 27.

[3] Macintyre, p. 28.

[4] Andrew Lycett, Ian Fleming, (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), p. 102.

[5] Sefton Delmer, Black Boomerang: An Autobiography: Volume Two, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1962), p. 70.

[6] Lycett, p. 133.