‘The celestial city is as real as any swamp’: Freya Stark in the Middle East

Document of the month: FO 898/114

Guy Woodward traces Freya Stark’s involvement in wartime propaganda

This memorandum appears in file FO 898/114, Special Operations Executive Activities. It is dated 15 July 1940 and records a meeting in Cairo between Freya Stark, the Assistant Information Officer to the Governorate of Aden (today part of Yemen), and Colonel Cudbert Thornhill, a veteran British intelligence officer who had served as military attaché in St. Petersburg during the Russian Revolution, where he had been involved in fomenting resistance to the Bolsheviks. Thornhill’s role in Cairo was to draft and disseminate propaganda to Italian-occupied North Africa and to Italian prisoners of war – he had been sent to Egypt in May 1940 by Department E.H. (this department preceded the SOE and PWE, and had primary responsibility for clandestine propaganda in the early months of the war).[1]

As a writer and explorer, Freya Stark was much celebrated for her travels in the Middle East during the 1920s and 30s. Her accounts of these were published to considerable success, but Stark’s adventures had also led to involvement with British intelligence – the War Office ‘made maps from her observations’ following her journeys to Lorestan and Mazandaran in Persia, and while working as a journalist in Baghdad she was given intelligence briefings on the Kurdish uprising of 1931-2 by a friendly British diplomat, which she published in The Times.[2] Her biographer Molly Izzard argues that Stark’s wartime career was a ‘logical continuation of her activities in the 1930s’.[3]

As war drew closer in August 1939, Stark travelled from her home in northern Italy to offer her services to the British state – she was employed by the Ministry of Information, first in London as an expert in southern Arabia. Later that year Stewart Perowne, public information officer in Aden, requested her transfer to work there on an Arabic programme of news broadcasts (Perowne and Stark later married, in 1947).

In East is West (1945) published at the end of the war, Stark describes this work in idealistic terms:

If one has a cause, and believes in it, one need not model oneself on Dr. Goebbels; the twelve apostles were more inspiring and more successful; and why should one’s voice waver merely from telling the truth? [We] wrote our bulletins believing in our news; and as it got worse and worse from April 1940 onward, we stressed the celestial city in the distance and pointed out with stronger emphasis the temporary nature of those swamps and thickets that lay in its immediate path. Luckily the celestial city is as real as any swamp.[4]

Stark was also involved in other white propaganda activities, including accompanying a travelling cinema which showed Ministry of Information films such as ‘Sheep Farming in Yorkshire’ and ‘Ordinary Life in Edinburgh’, in addition to newsreels depicting British military strength.[5] She also seems to have engaged in some unofficial covert propaganda activities: observing that the head of the Fascist mission in San’a resembled a pig, she spread insults about him among the harems of the city.[6]

Stark’s fluent Italian proved useful following the Italian entry into the war – she claims in East as West that her translations of documents taken from a captured Italian submarine enabled further successful anti-submarine operations. She also conducted interrogations of Italian prisoners, breaking regulations by allowing the men to write letters home before questioning, in the belief that this produced more valuable intelligence.[7]

Stark travelled to Cairo in summer 1940, and embarked upon her best-known wartime propaganda campaign, establishing a group of young Arab men called the Brotherhood of Freedom, which attempted to foster support for British war aims through meetings and publications proclaiming democratic ideals. Her claims regarding the success of the Brotherhood campaign were bold: she argued that it had fostered democratic feeling of ‘genuine quality’, and justified its existence by maintaining pro-British sentiment in the months before the battle of El Alamein, when Axis forces menaced Alexandria and Cairo.[8]

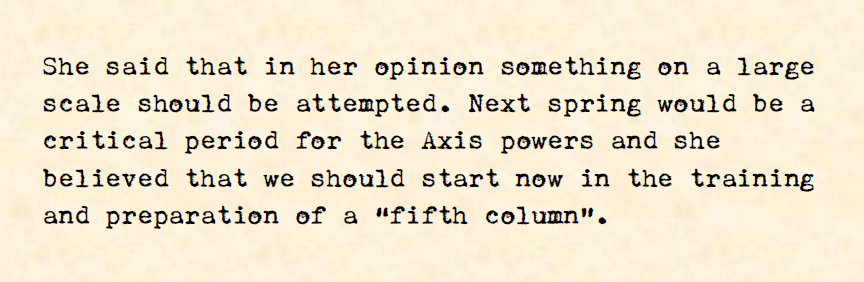

As this document shows, however, Stark also contributed to the development of anti-Italian propaganda activities. It records that ‘Miss Stark, who has lived many years in Northern Italy, said that she had very definite views on this subject, believing that the objective should be approached with subtlety and by the use of cumulative effects.’ Stark and Thornhill also discussed newspaper propaganda, and plans to circulate a pro-Allied publication Giornale d’Orient in Italian North and Eastern Africa, before moving on to the question of prisoners, upon which Stark ‘expressed her own theory’:

Referring to her experiences of interrogating prisoners in Aden, Stark argued that the Italian armed forces contained relatively few hardcore fascists (in East is West she suggests only one third were fascist, and that another third were hostile to Mussolini). However, she feared that imprisoning pro and anti-fascist Italians together under harsh conditions would threaten what she interpreted as ‘the friendly disposition’ of the anti-fascists towards the British authorities.

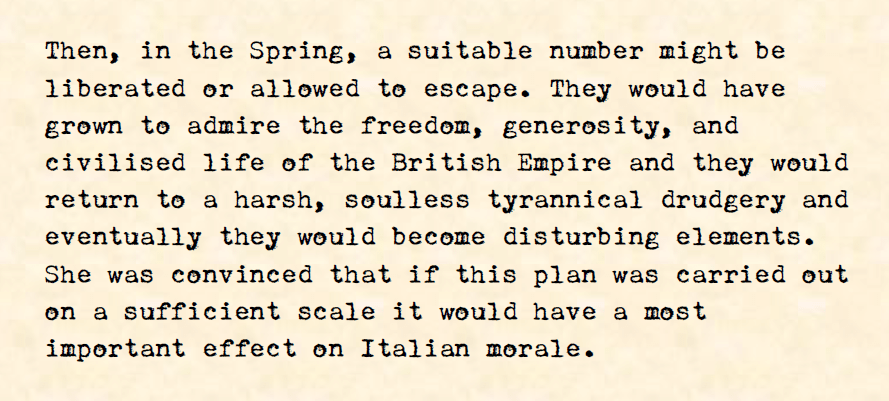

Accordingly Stark advocated a radical plan, of imprisoning non-fascists separately, treating them ‘with the greatest courtesy and consideration’, and exposing them over a long period to pro-British propaganda:

The meeting, which concluded after some discussion of leaflet propaganda, is recorded as a ‘very satisfactory preliminary conference’. Indeed, the following month Stark and Thornhill co-authored a joint printed memorandum on anti-Italian propaganda (FO 898/113) which reflects this discussion and expressed hopes that by quarantining committed fascist POWs, other Italians could be turned against Mussolini’s regime and made into a Fifth column to spread pro-British ideas and even to act as ‘agents’.

If this plan seems over-ambitious, that is because it was. The discussions recorded here are likely to have fed into the abortive campaign known as Operation Yak, developed between Thornhill and MI (R)’s Peter Fleming (brother of Ian) with enthusiastic encouragement from Hugh Dalton, the minister in charge of SOE, and which aimed to screen Italian POWs in North Africa and recruit them into SOE to run missions, but failed when not a single Italian volunteered for service.[9] As with many tales of special operations in the early stages of the war, this was fated to be a cautionary tale of enthusiastic amateurism.

While compelling and dramatic, Stark’s wartime career is illustrative and representative of a contradiction central to any study of British deployment of covert propaganda. This can be observed in the palpable tension, both in her published memoirs and in this particular document, between Stark’s professed and often-proclaimed faith in idealistic and nebulous concepts such as British values or Western democracy (eg ‘the celestial city in the distance’ or the ‘civilised life of the British Empire’) and the shady and deceptive means used to promote these abstractions.

Notes

All archival material is Crown Copyright and is held in The National Archives. Quotations which appear here have been transcribed by members of the project team.

[1] Nigel West, Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence (Lanham etc.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), p. 655. For Thornhill’s role in Egypt see FO 898/116. Thanks to psywar.org for pointing this out.

[2] Peter H. Hansen, ‘Stark, Dame Freya Madeline’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (https://doi-org.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/38280).

[3] Molly Izzard, Freya Stark: A Biography (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993), p. 133

[4] Freya Stark, East is West (London: John Murray, 1945), pp. 13-14.

[5] Stark, East is West, p. 33.

[6] Stark, East is West, p. 32.

[7] Stark, East is West, p. 45-6.

[8] Stark, East is West, p. 92.

[9] West, Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence, p. 655; see also Roderick Bailey, Target: Italy: The Secret War Against Mussolini 1940–1943 (London: Faber and Faber, 2014). MI (R) refers to Military Intelligence (Research), created in 1938 as a War Office unit ‘dedicated to the study of unorthodox or irregular tactics’ (West, Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence, p. 391).