DON’T drink yourself silly in public: the PWE’s pocket guide to France

Document of the month: FO 898/478

Guy Woodward on the PWE’s pocket guides for service personnel

This small 64-page booklet measures 10.5 x 13.5 cm. Its blue and white cover features a picture of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and the single word title ‘France’. On first glance it appears to be a tourist guide, but the booklet was in fact produced by the PWE for Allied service personnel deployed to France following the D-Day landings of June 1944.

The PWE’s primary function was to produce propaganda for enemy and occupied Europe, a role which required substantial and intensive intelligence work to ensure that broadcasts, leaflets and publications were targeted at specific countries, regions and localities. The expertise and knowledge thereby gathered, however, meant that the PWE was ideally placed to produce pocket guides such as these, introducing servicemen to French history, culture, customs and conventions – and teaching them some basic phrases in French, with phonetic pronunciation guides (‘Seal vous play, mairsee’).[1]

In addition to France, the PWE collection in the National Archives contains drafts or printed copies of pocket guides for Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Other documents show that guides to Albania, Greece and Hungary were also drafted or planned. Some were presumably never printed or distributed: in the cases of Hungary, Romania and Yugoslavia, for example, the advance of the Soviet Union meant that British troops never entered these countries in significant numbers.

The archive shows that editions varied slightly depending on the intended readership. As the maple leaf on the cover suggests, the pocket guide to France pictured above is addressed to Canadian troops – the draft version of the guide in the same file shows that only perfunctory changes were made to adapt the text however, as in most cases ‘Britain’ or ‘British’ is simply replaced by ‘Canada’ and ‘Canadian’.

The text is addressed to an individual reader throughout, seemingly in an attempt to emphasise the importance of personal responsibility. The opening paragraph reads:

A new B.E.F. [British Expeditionary Force], which includes you, is going to France. You are to assist personally in pushing the Germans out of France and back where they belong. In the process, you will meet the French, maybe not for the first time. You will also, almost certainly for the first time, be seeing a country which has been subjected to German occupation for several years. This is a point worth fixing in your mind. You will learn what it means.[2]

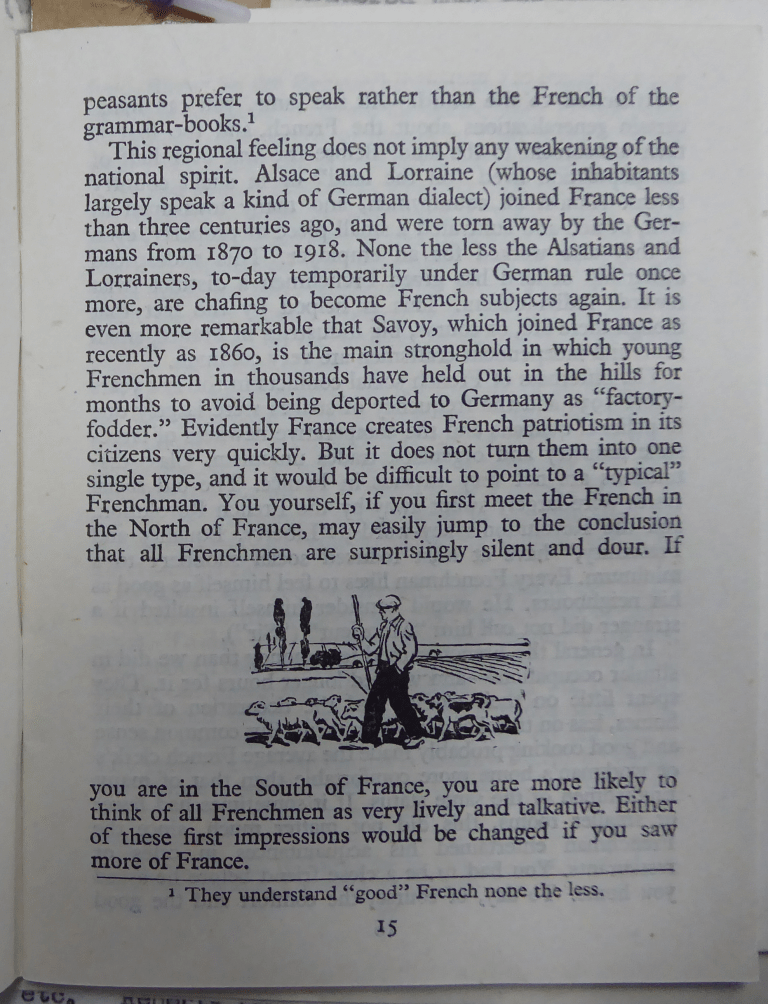

After a hasty canter through French history from the Roman invasion to the present day, the booklet poses the question ‘What are the French People Like?’, observing that despite a palpable ‘strong national feeling’ regional identities and characteristics remain important and that ‘it would be difficult to point to a “typical” Frenchman.’[3]

The guides are heavily dependent on generalisation and essentialist descriptions of national characteristics, and perpetuate some troubling stereotypes. The guide naturally assumes an exclusively male readership, and the misogyny of some sections makes for uncomfortable reading today. Under the heading ‘Not Like Montmartre’, the guide advises that ‘it is as well to drop any ideas about French women based on stories of Montmartre and nude cabaret shows’, and that ‘If you should happen to imagine that the first pretty French girl who smiles at you intends to dance the can-can or take you to bed, you will risk stirring up a lot of trouble for yourself – and for our relations with the French.’[4]

The guide repeatedly pleads with readers to consider themselves as representatives of their country and to behave with sensitivity, suggesting that ‘The good guest retains his welcome by making himself as little trouble as possible and doing all he can to help his hosts’; with reference to the recent German occupation it advises that ‘if you’re too boisterous and noisy it will be rather like doing a step-dance in front of a man who has just had his legs off.’[5] Discussions on the subjects of religion and politics are strongly discouraged, and alcohol is repeatedly raised as a possible source of conflict and tension:

DON’T drink yourself silly in public. If you get the chance to drink wine, learn to “take it.” The failure of some British troops to do so was the one point made against our men in France in 1939-40 and again in North Africa.[6]

The second half of the guide features phrases and vocabulary intended to help service personnel communicate with local people. It observes:

The French are politer than most of us. Remember to call them “Monsieur, Madame, Mademoiselle,” not just “Oy!” And don’t forget “S’il vous plaît” (please) and “Merci” (thank you).[7]

In 2005 the Bodleian Library republished the guide under the title Instructions for British Servicemen in France, 1944. Appearing between stiff, olive green covers, with the new title printed on the cover in austere sans serif capitals, it has a more strikingly military appearance than the printed copy in The National Archives pictured above. The reprint dispenses with most of the French words and phrases, and also omits the illustrations which are scattered through the wartime edition.

A preface by the historian and archivist Mary Clapinson states that the guide was discovered in the papers of its author, the journalist Herbert David Ziman, which were donated to the Bodleian in 1995; Ziman was on secondment to the PWE from the Intelligence Corps in 1943 when he wrote the booklet.[8]

The Bodleian reprint has proved highly popular and is widely available from bookshops and museums as a stocking filler for military history enthusiasts. Perhaps unexpectedly, the guide also found a readership in France: in 2006 a French translation of the guide was published by the small Parisian house Les Quatre Chemins and reportedly sold well.[9] Quand Vous Serez En France featured an introduction by the journalist Pierre Assouline, expressing fascinated bemusement at the ‘battledress paperback’ produced with ‘a consummate sense of understatement’ and which helps explain the continuing attraction of France for the British.[10] Turning to the final section of the guide, he suggests that in phonetically transcribed phrases such as ‘Bonjewer, commont-aalay-voo?’, French readers will find ‘an original form of poetry.’[11]

This is the first post in an occasional series – subsequent posts will address pocket guides to other countries.

Images by kind permission of The National Archives.

Notes

[1] ‘Draft Soldiers’ Guide to France’, FO 898/478, p. 31.

[2] Ibid., p. 2.

[3] Ibid., p. 14.

[4] Ibid., p. 17.

[5] Ibid., p. 26, p. 28.

[6] Ibid., p. 29.

[7] Ibid., p. 28.

[8] Instructions for British Servicemen in France, 1944. (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2005), n.p.

[9] Noam Cohen, ‘For British Troops, Help Crossing the Channel’, The New York Times, 2 July 2006: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/weekinreview/02word.html

[10] Quand Vous Serez En France (Paris: Quatre Chemins), p. 11, p. 16.

[11] Ibid., p. 17.