‘Show it only to your intimate friends’: circulating propaganda behind enemy lines

Document of the month: FO 898/449/259

Guy Woodward on the reception of propaganda leaflets in enemy and occupied Europe

Most of our research so far in this project has focused on the production of propaganda, and specifically on the writers and artists involved in the work of the Political Warfare Executive. Accounts of PWE service by Sefton Delmer, David Garnett and Ellic Howe describe the preparation of leaflets, booklets and other publications which were printed in England before being dropped by the Royal Air Force over enemy and occupied Europe.

The files in the National Archives at Kew contain many examples of printed propaganda, including leaflets, magazines and newspapers – you can also view many of these online on the invaluable website psywar.org.

But what of the readers of these publications? It is hard enough trying to piece together the activities of a covert branch of the British state, even with the benefit of archival records and collections, and autobiographical recollections of the time. It is even harder, and often impossible, to trace what happened to propaganda publications once they had fallen to the ground in Germany, France, Belgium or Bulgaria. This month’s document offers some clues, however.

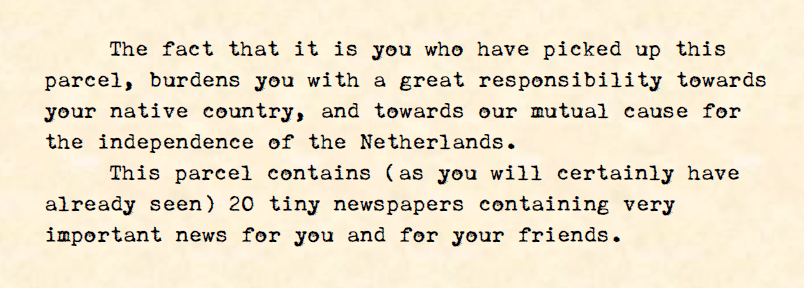

A draft of a letter dated 2 September 1940, it is addressed ‘To an Unknown Fellow-Countryman’ and was intended to accompany newspapers for circulation in the Netherlands – it appears towards the end of file FO 898/449, ‘Leaflets For Netherlands: Correspondence’. It addresses the recipient ‘Dear Friend’, and states that

The letter continues to request that the recipient distribute these newspapers to persons known and unknown, and makes ten suggestions for how this might be done:

Somewhat patronisingly, the letter continues to advise that ‘We know that every Dutchman can think out a dozen more methods, and we expect you to do your duty in the interest of our common cause’, and cryptically suggests that the second edition of the newspaper ‘will reach you in quite a different way. Look out for it.’ The letter, signed ‘The Friends’, concludes with cheers for Queen Wilhelmina and for the ‘Free Netherlands’.

It is striking how the letter seeks to appeal to the vanity of the Dutch recipient, flattering their ingenuity and assuring them that in passing on the newspapers they will be courageously performing an important service. We do not know if the letter was sent in this exact form, but the draft certainly gives some insight into how propaganda materials might have been disseminated once they had been dropped from the air.

Propagandists were clearly concerned to establish how British propaganda was being distributed and received: there are several files in the archive which report reactions to leaflets in enemy and occupied zones. Reports were often gathered from intelligence sources in the field, such as Special Operations Executive agents. One report in March 1940 claimed that a newly trodden path had been discovered in a forest in Germany, leading to a tree on which a leaflet had been pinned.[1]

Reports from Belgium in 1943, meanwhile, claimed that leaflets dropped by aeroplane ‘had a tremendous effect on the morale of the people and were greatly appreciated’; in France a man found a packet behind his factory during his lunch hour and distributed them to his workmates; in the Netherlands several complaints had been voiced that not enough printed materials were being sent and a thriving black market in British magazines had developed, with copies changing hands for as much as £2. 10s – in some areas ‘those who have been lucky enough to get hold of a few hire them out to those less fortunate.’[2]

As noted in earlier posts, the RAF was sceptical regarding the value of airborne propaganda and often reluctant to risk aircrews and aeroplanes to deliver leaflets. Observations from the field were also sometimes negative and discouraging: one SOE agent reported from France in April 1943 that in the course of extensive travels they had not seen any British leaflets, and did not believe that the French were willing to face prison for being found with a propaganda leaflet in possession. Leaflets were, the agent stated, a ‘sheer waste of paper, time and money.’[3]

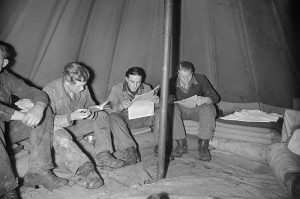

Prisoners of War were also valuable sources of information regarding reactions to propaganda: during interrogations many were questioned on their exposure to British propaganda newspapers or radio broadcasts. In late December 1944, for example, 2350 German POWs were surveyed to establish how many had encountered the PWE newspaper Nachrichten für die Truppe while in combat – it was discovered that 96 had seen the newspaper and of these all but six had read its contents. It was also discovered that, contrary to German regulations, very few of the newspapers were turned in or destroyed once found – over 70% of POWs who had read the newspaper passed it on to another soldier. The PWE estimated that each copy of reached over three German soldiers.[4]

Over the course of the war methods of dropping printed materials from the air were refined, but inevitably many were wasted. Towns and cities were problematic: many leaflets ended up on roofs where they were inaccessible, or dropped in streets where citizens, fearful of punishment, were reluctant to pick them up: mindful of this, a 1943 PWE directive suggests that leaflets for enemy territory must convey their meaning at first glance, so they could be understood immediately and would not even need to be picked up.[5] Conversely, as Garnett recalls, ‘dwellers in lonely places’ were more likely to be able to pick up and circulate leaflets without being caught.[6]

One leaflet intended for Hungary in 1944 made an ingenious attempt to circumvent laws designed to prevent the circulation of Allied propaganda. This was a postcard addressed to police officers, advising them that if they were enforcing the orders of the German-backed Hungarian government they were acting as ‘Enemies of the People’. The card advised anyone who found it to send it to any ‘policeman or gendarme’ they knew, and featured the reminder: ‘Don’t forget that you are acting in accordance with official instructions if you surrender all foreign leaflets to the competent authority.’[7] The leaflet was intended to undermine the police; paradoxically, however, it was perfectly legal to circulate.

Notes

All archival material is Crown Copyright and is held in The National Archives. Quotations which appear here have been transcribed by members of the project team.

[1] David Garnett, The Secret History of PWE: The Political Warfare Executive 1939-1945, (London: St Ermin’s Press, 2002), p. 30.

[2] FO 898/437.

[3] FO 898/435.

[4] FO 898/452.

[5] FO 898/458.

[6] Garnett, p. 190.

[7] FO 898/123.