Voici l’ordre nouveau!: pop up propaganda

Document of the month: FO 898/514

This leaflet appears in the file ‘PWE French leaflets and booklets’ – produced for occupied France in 1941, it is a striking and unusual example of three-dimensional printed propaganda.

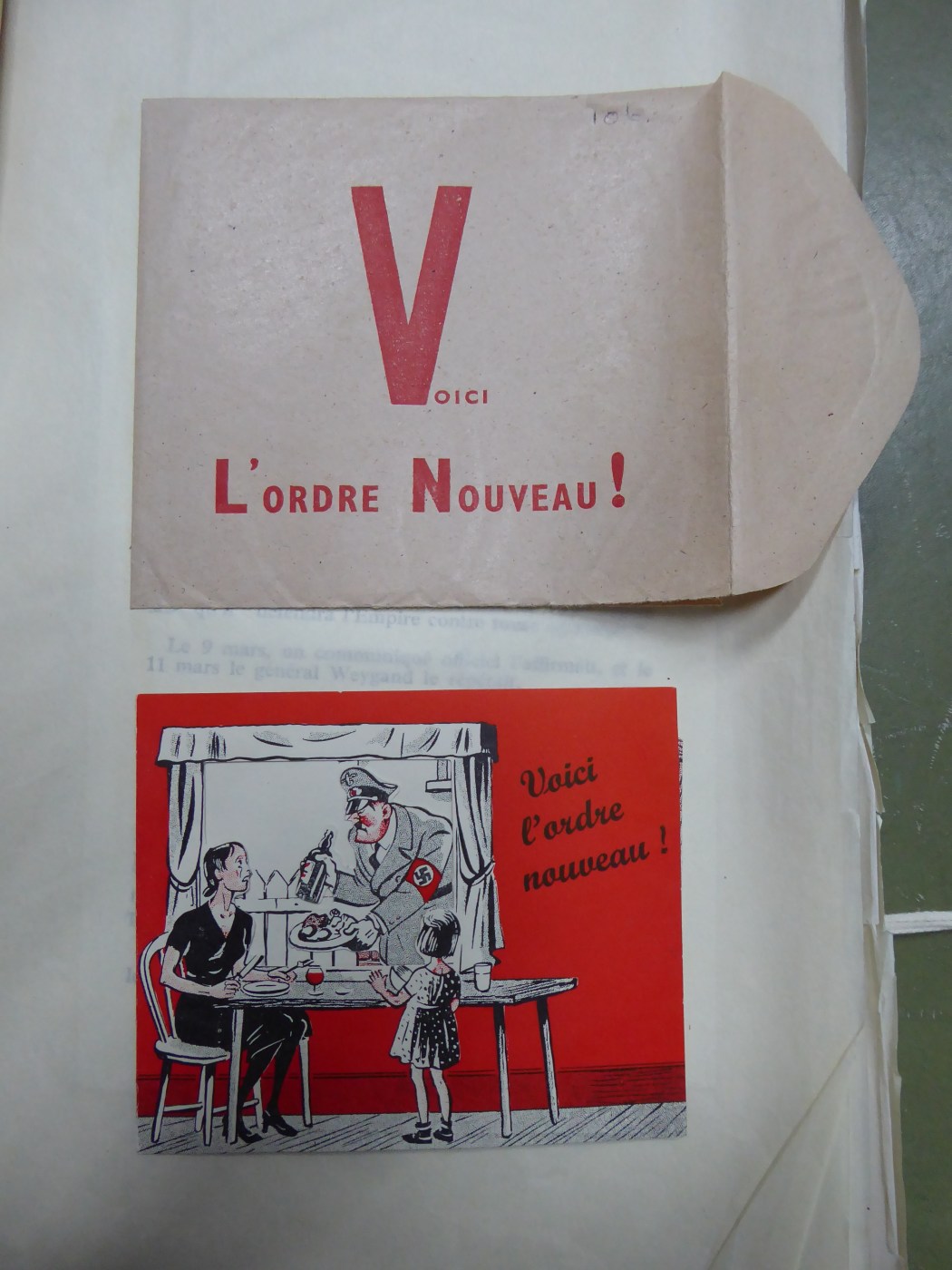

The leaflet is made of card and is small – 12 ½ by 10 cm – it is enclosed within a pale brown envelope bearing the message ‘Voici l’ordre nouveau!’ in red, translating as ‘Here is the new order!’ The V of ‘Voici’ is elongated and centred, aligning this propaganda with the ‘V’ campaign which spread across France, Belgium and the Netherlands in 1941. This was initiated by Victor de Laveleye, exiled Belgian Minister of Justice, who suggested in a January 1941 radio broadcast that Belgians could use the letter ‘V’ – standing for ‘victoire’ in French and ‘vrijheid’ in Flemish – as a sign to symbolise defiance to the German occupiers and faith in eventual liberation.

PWE’s John Baker White recalled that the ‘V’ sign – later indelibly associated in Britain with Winston Churchill, of course – could soon be found scrawled on walls, painted on the side of ships and locomotives, and even chalked on the backs of German soldiers in cinemas and crowds. On washing days, he writes ‘country women would lay out the sheets and clothes in Vs on the fields as messages to the R.A.F.’[1]

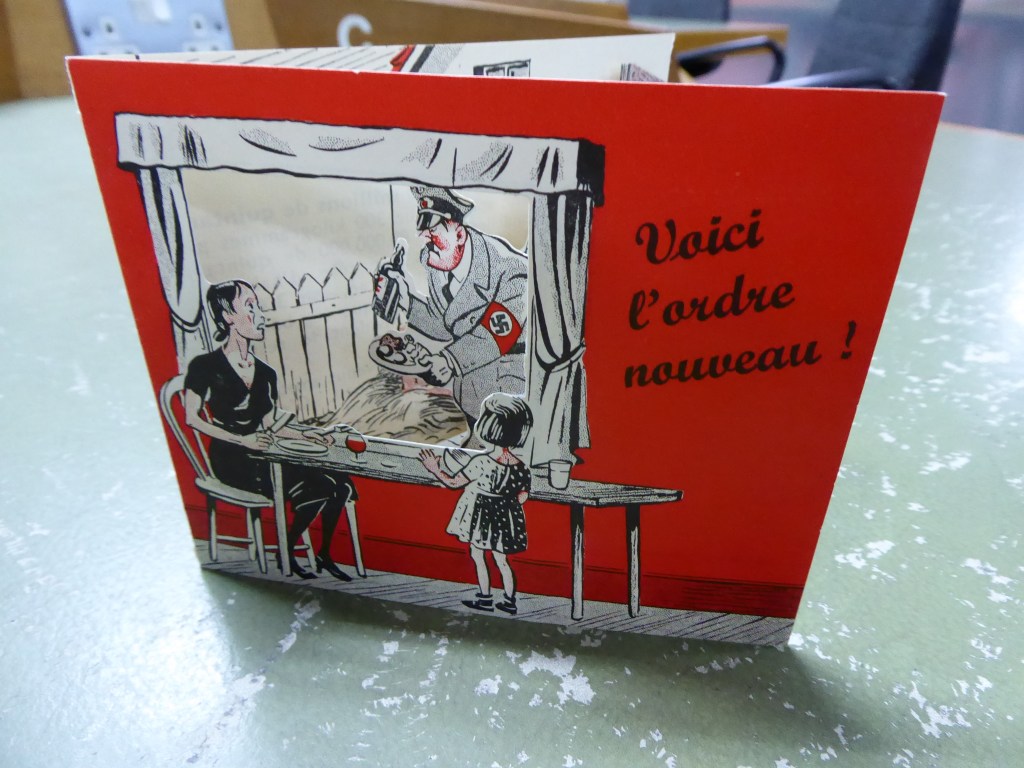

The front of the card shows a woman sitting at her dining table, watching helplessly as a red-faced cartoon figure of Hitler reaches in through the window to remove a full plate of food and a bottle of wine, leaving the table almost bare. A small child looks on. The caption repeats the words on the envelope – ‘Voici l’ordre nouveau!’ – but it is now clear that these are heavily ironic.

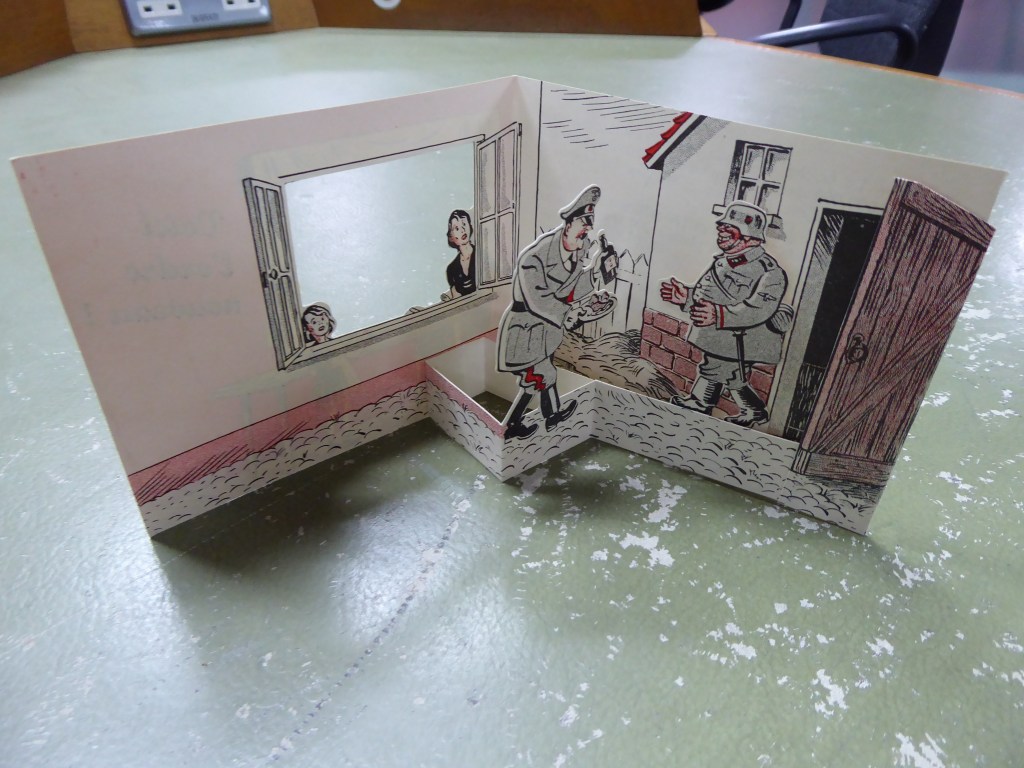

When the card is opened the figure of Hitler flips round, and appears to walk away from the open window towards a corpulent German soldier who emerges from a barn grinning and with outstretched arms, ready to receive the food and wine. The woman and her daughter look on disconsolate.

The online resource Psywar.org states that just 1200 copies of the card were produced by PWE’s predecessor organisations E.H. and S.O.1; it was dropped on one occasion only, the night of 30 September-1 October 1941. Another version was produced in Flemish for Belgium and the Netherlands (a copy of this can be found in the PWE archive in file 898/507) – there was also apparently a version in Arabic.

It is not clear how many similar leaflets may have been produced, but historian of wartime propaganda Charles Cruickshank mentions the production of ‘ingenious trick folders which when opened showed an animated Hitler in unflattering situations.’[2]

The aesthetic may appear broadly familiar to British viewers – the incongruous intrusion of a caricatured Hitler into a quotidian everyday scene also featured in Home Front propaganda at this time, as shown by Fougasse’s 1940 ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ posters, in which Hitler and Goering eavesdrop on gossiping travellers on public transport.

Although comic on first glance, the card makes a serious point – that occupying German forces are consuming local resources to the extent that the French population is going hungry. The reverse of the card expands on this, claiming that the occupiers are extracting goods to the value of 400,000,000 francs per day, causing inflation and ruining French finances. Using statistics, the text here details German seizures of potatoes and corn, and laments the move by German beer-drinking soldiers to become consumers of French wine. ‘Le boche mange – le français regarde – Voici l’ordre nouveau!’ it concludes – ‘The Boche eat – the French watch – here is the new order!’

The intricate nature of the design and the use of colour perhaps conveys a further hidden message, however – historian Tim Brooks has described how the use of high quality materials, colour and design in printed propaganda was an important means of demonstrating that the Allies were well-resourced at a time of extreme scarcity.[3] Recipients might reason that if the Allies could spare quality paper and ink for leaflets, they were also likely to possess the material resources required to win the war.

Images by kind permission of The National Archives

Notes

[1] John Baker White, The Big Lie (London: Evans Brothers, 1955), p. 89.

[2] Charles Cruickshank, The Fourth Arm: Psychological Warfare 1938-1945 (Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 97.

[3] Tim Brooks, British Propaganda to France, 1940-1944: Machinery, Method and Message (Edinburgh University Press, 2007), p. 113.