Adolf and His Donkey Benito

Document of the month: FO 898/128

Guy Woodward on Kem’s cartoons for North Africa

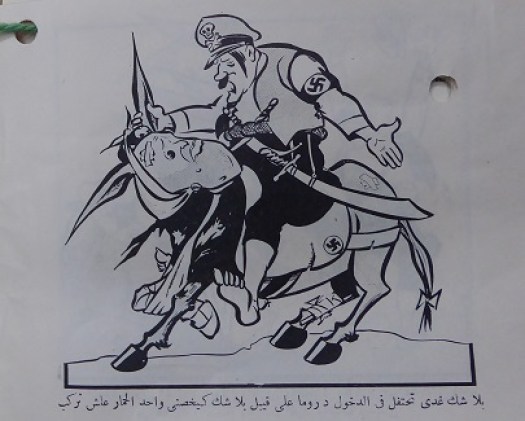

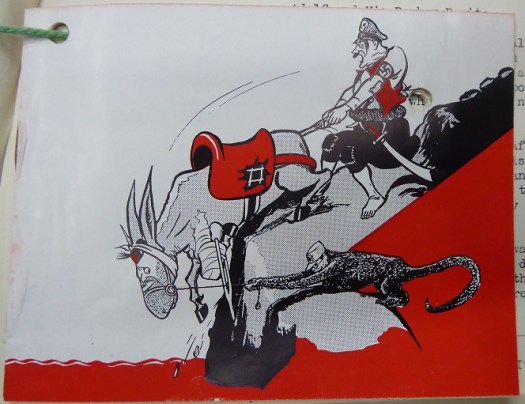

‘Adolf and His Donkey Benito’ is an Arabic-language cartoon booklet produced by PWE for distribution in North Africa in 1942 – it appears in file FO 898/128, ‘Propaganda Activities, Leaflet Translations (Arabic)’. Satirising the relationship between the German and Italian dictators, the booklet depicts the Führer as an unkempt and increasingly deranged figure, exasperated and frustrated in his attempts to train a recalcitrant donkey – whose face bears a strong resemblance to that of Mussolini. In line with many other examples of Allied propaganda attacking Mussolini, the donkey is portrayed as cowardly, incompetent and hapless – the animal is shown suffering a range of injuries.

The file features English translations of the Arabic text and captions. The introduction states that the story’s protagonist ‘used to be a housepainter, who worked his way up the ladder until he reached the position of Dictator of Germany. This was done by means which it would not be decent to print in this book.’ It continues to recall that as a housepainter Adolf ‘could not afford more than one shirt’ and ‘had to stay in bed whilst his only shirt was being washed.’ However, once he became dictator ‘he bought a shirt for everyone who accepted him as leader. He chose the colour brown for the shirt in order that dirt would not show quickly and bloodstains would be less apparent.’ In due course, the introduction concludes, Adolf met the donkey Benito. The two ‘set out to conquer the world, and in the following pages you will see some of their adventures.’

In some frames other Nazi and Axis figures appear. On the front cover a monkey wearing a military cap adorned with the Japanese rising sun helps Hitler prevent the donkey tumbling into a river. When a grotesquely obese Hermann Göring – whose tattered black wings are a mocking reference to Göring’s role as Supreme Commander of the Luftwaffe – attempts to sit on the donkey, the beast collapses to the floor.

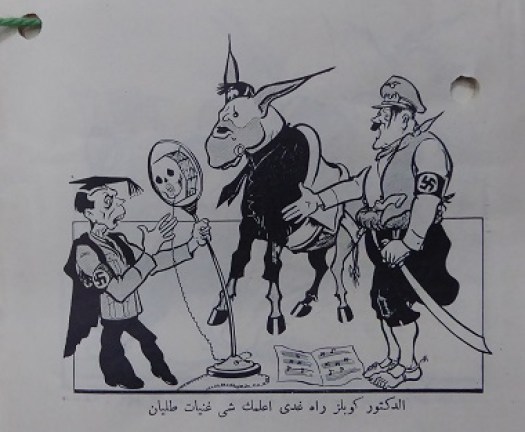

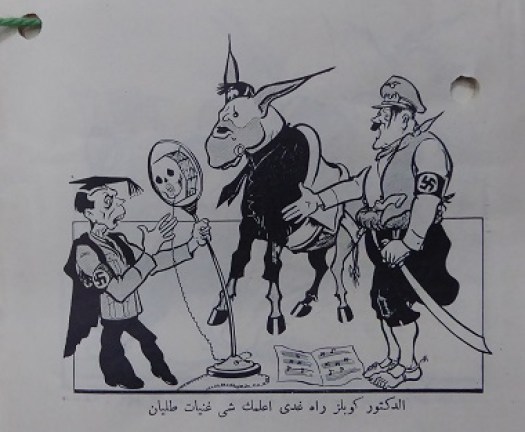

Later Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, dressed in mortar board and gown, attempts without success to train the donkey to sing into a microphone.

The booklet consists of eighteen cartoons, all in black and white apart from the outside covers which also feature red – the colour scheme resembles that of the pop-up cartoon Hitler leaflet examined in a previous post. Both publications demonstrate the important role played by cartoons in transnational propaganda: caricatures of immediately recognisable figures as Hitler and Mussolini had an unparalleled ability to transcend borders and cultures.

The artwork for both publications is by Kimon Evan Marengo (KEM), a Cairo-born Anglo-Greek cartoonist and journalist who produced large quantities of visual propaganda for the Ministry of Information and PWE for North and West Africa and the Middle East during the war. He drew several versions of ‘Adolf and His Donkey Benito’, and even produced an animated film featuring the popular caricatures: storyboard sketches for this are displayed in a fascinating exhibition of wartime cartoons currently showing at the University of Kent’s Templeman Gallery. Kem’s papers can be found in the British Cartoon Archive at Kent.

The file in the PWE papers features an intriguing detail regarding the circulation of the leaflet. A memo dated 18 July 1942 sent by PWE’s Sylvain Mangeot to Hracia Paniguian of the French Section outlines a recent meeting with a ‘Mr Quennell’, who reported that:

Kem’s booklet with Hitler and his donkey, Mussolini, was in the bags which were blown up by the German bomb on the quay at Tangier. The leaflets were scattered and the local inhabitants snatched them and they are now on sale, and Mr. Kem’s caricatures seem to have taken very well indeed.

This anecdote hints at the significance of distribution methods for the credibility and appeal of printed propaganda. We can infer that material which circulated on a commercial or illicit quasi-commercial basis appeared more detached from the official Allied propaganda machine, and thus appeared more authentic. The PWE do seem to have understood this: as the war turned in the Allies’ favour the organisation began producing publications for liberated territories, and arranged for cultural and indirect propaganda – such as the French literary digest Choix – to be distributed through commercial venues such as bookshops and kiosks.

Images by kind permission of The National Archives

The exhibition Keep Smiling Through: British Humour and the Second World War explores the use of humour in cartoons, letters, books, ephemera and artefacts from the First and Second World Wars. It complements the symposium of the same title held at the University of Kent on 12–13 September 2019 and was curated with the assistance of Special Collections & Archives’ inaugural exhibition interns.